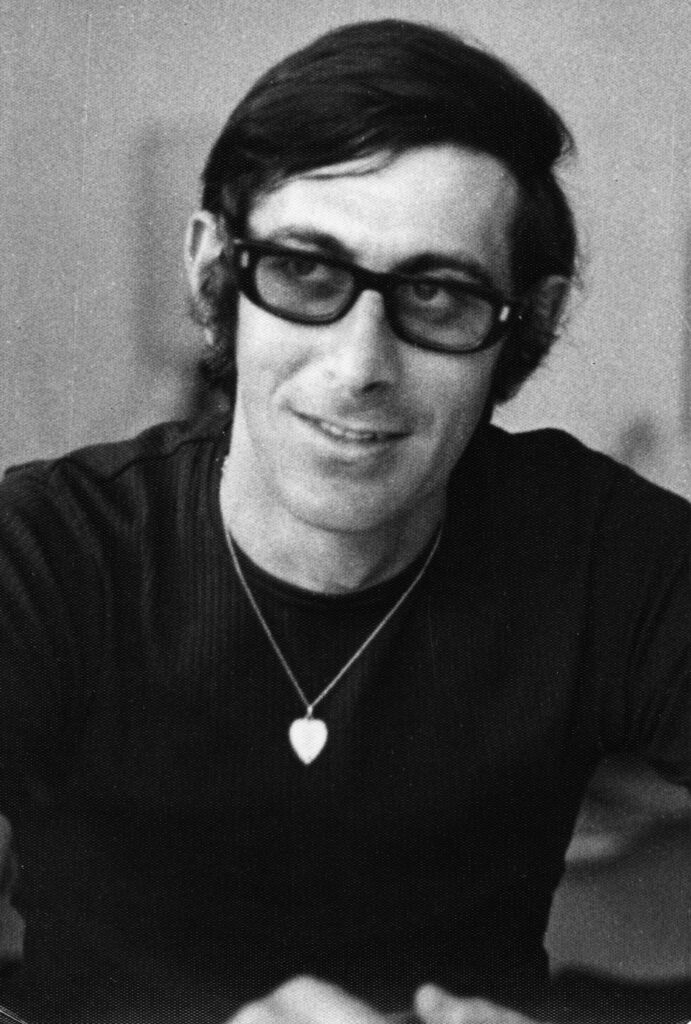

Andrei Spitzer was born on July 4, 1945 in Timișoara (Romania), the son of Shoah survivors Eleonora, née Hirshel, and Tiberiu Spitzer. His sister Judith, five years his senior, was a rower, and Andrei started fencing at the age of nine. When he was eleven he lost his father to cancer and his mother had to work hard to provide for her children. Andrei trained in the electrics sector and, as a fencer, enjoyed considerable success at tournaments. His mother, however, did not see a future for him in Romania. As a result, Andrei and Eleonora Spitzer emigrated to Israel in 1964. Judith had married in the meantime and stayed in Romania.

It was not easy to find a foothold in their new homeland which was still a fledging country. Andrei Spitzer and his mother first had to learn Hebrew. Soon after his arrival, Andrei began his compulsory military service and, in the process, not only learned Hebrew quickly, but was also able to continue his fencing training at Maccabi Ramat Gan. In 1968, the Israeli Fencing Federation sent him to the Netherlands to be trained as a coach at a sports academy and to be able to work as a national coach after his return. He was quick to learn Dutch and taught fencing alongside his studies.

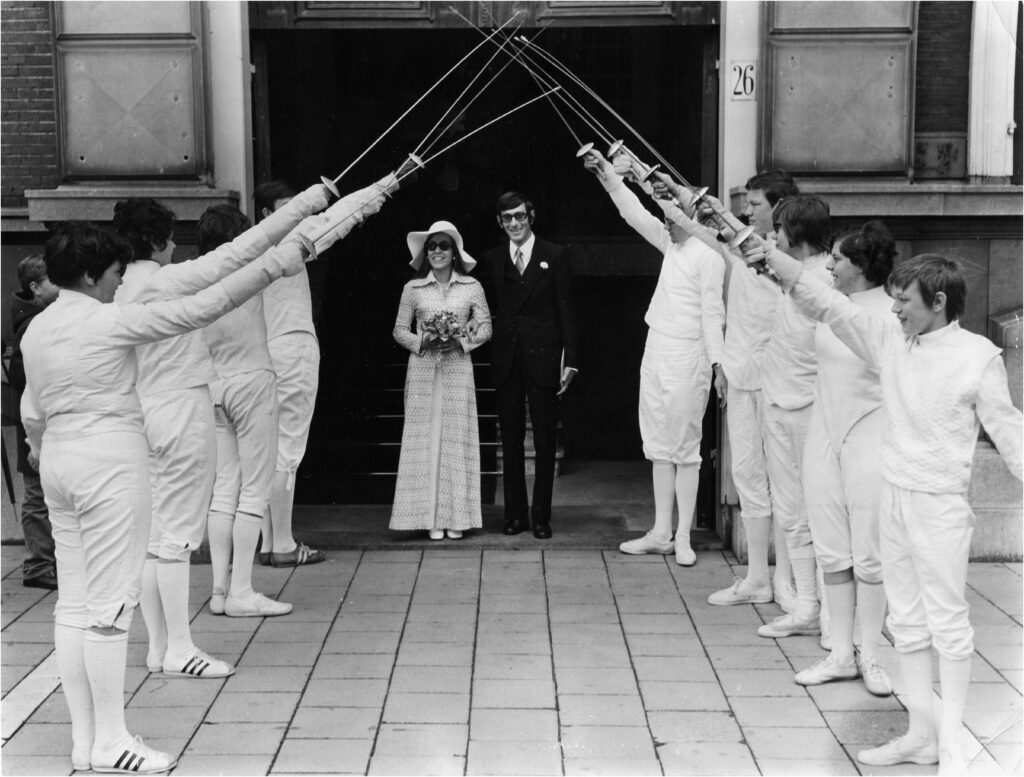

One of his students was Ankie, who has lived a large part of her life in different countries and caught Andrei’s attention when she said how exhausted she was in training in Hebrew. He fascinated her by always surprising her, time and again, during the conversations they had together with his way of seeing things and his knowledge, in a way that no one in the whole world had ever done before, Ankie said later. She went on to describe him as a quiet, peace-loving person who taught her not to make judgments about others too soon. A few months before his planned return, the two became a couple and decided to move to Israel together. Andrei Spitzer was to head a new sports center in the north of the country, in Biranit. The couple lived happily in the remote area on the Lebanese border, first marrying in a civil ceremony in the Netherlands and, after Ankie had converted to Judaism, in Israel.

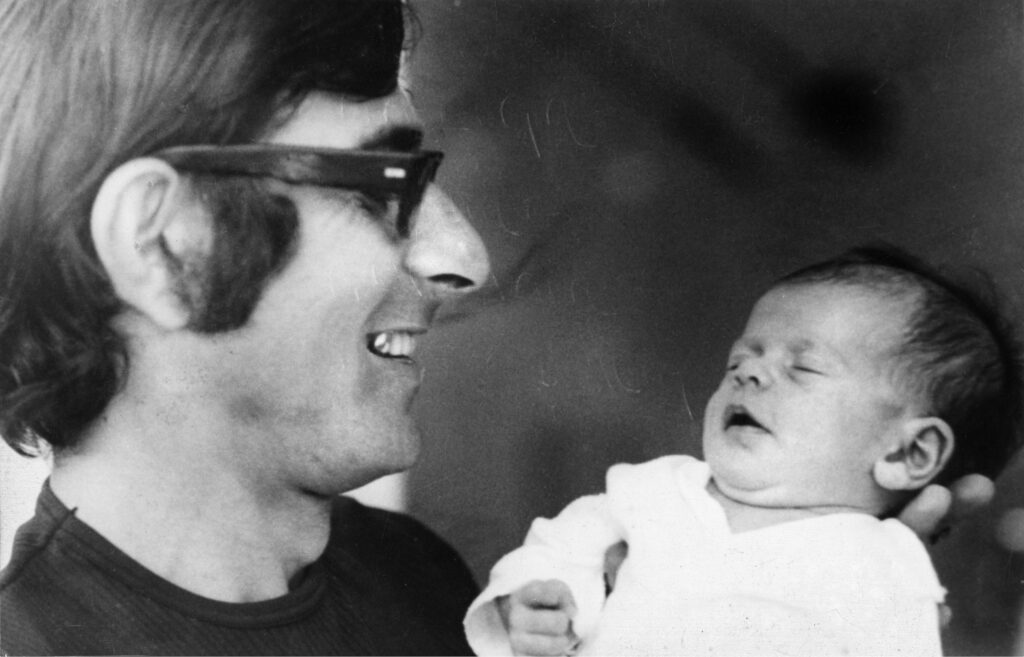

At the beginning of 1972, the sports center was incorporated into the Wingate national center for sports in Netanya. Andrei Spitzer worked there as head fencing coach, campaigned for disadvantaged youths, and collected fencing equipment to give to those who could not afford the expensive equipment themselves. When he was sent to the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich as the fencing coach of Yehuda Weinstain and Dan Alon, a lifelong dream of his came true. The birth of his daughter Anouk two months before the Games made him even happier.

Ankie and Andrei Spitzer traveled to Munich with the Israeli Olympic delegation and took a room in a guest house to be together. Nevertheless, both of them went in and out of the Olympic Village day and night, watched competitions and enjoyed the international atmosphere. The feeling of surmounting borders and political conflicts which prevailed among the international sports delegations was, according to his wife, a source of great joy to Andrei Spitzer.

After the fencing competitions the couple went to the Netherlands to visit their daughter who was sick and being cared for by her grandparents. Like his wife, Andrei Spitzer would have liked to have stayed longer, but he only had two days leave. He just managed to catch the train to Munich and returned to the Olympic Village shortly after midnight the next day, September 5, 1972. Only a few hours later the apartment was attacked by terrorists. In the morning his family learned of the hostage-taking in the media, and 24 hours later of his death. His widow Ankie then traveled to Munich and, despite being warned not to, went to the apartment where her husband and his colleagues had been held hostage. She picked up “Waldi,” the dachshund soft toy mascot which her murdered husband had bought for his daughter Anouk, and took it with her. It was stained with blood.

Andrei Spitzer was buried two days later in Kiryat Shaul Cemetery in Tel Aviv after his mother Eleonore had returned from Romania. The survivors of the Munich massacre at the Summer Olympics all agree that they want to raise their children without hatred.

Andrei would not have allowed anything violent … his ideal [was] to make something positive out of something negative.

Andrei Spitzer’s widow, Ankie

Today Andrei Spitzer’s grandson is an enthusiastic fencer.

Text: Angela Libal; research: Piritta Kleiner, Curator, Memorial to the 1972 Munich Massacre, Bavarian Ministry of Education, Science and the Arts

TWELVE MONTHS – TWELVE NAMES

50 Years Olympic Massacre Munich

50 years after the Munich Summer Olympics, the Munich Massacre of September 5–6, 1972 is to be commemorated throughout 2022. Every month is dedicated to one victim. A variety of different actions in public spaces is planned, ranging from installations lasting the entire month to activities on one specific day.

October

In October, the Christian Springer “Initiative Schulterschluss” is dedicating a youth exchange to Andrei Spitzer, as well as a commemorative tournament on October 23, 2022, in the Sports Center in Häberlstrasse and a design competition at the Berufsschule für Farbe und Gestaltung (Vocational School for Color and Design). Two motifs chosen from among competition entries can be seen in October on billboards and flagpoles around the city. They are intended to keep memories alive, to anchor the lessons learned from the events of 1972 in the minds of those living in Munich, and to encourage people to take a stand against violence.

As part of mediation work at the Jewish Museum Munich, four groups of young people have intensively and very creatively developed various ways to commemorate Andrei Spitzer. These projects will be presented during the “Long Museum Night in Munich” and will then be on display at the Jewish Museum Munich until October 30, 2022.