Mark Slavin was born on January 31, 1954, in Minsk, at that time in the Soviet Union, now in Belarus. He was the first child of the young couple Anna and Jakob Slavin. A brother and a sister followed in 1956 and 1964. They grew up relatively privileged, as their grandfather, Grisha Chernyak, had distinguished himself in the Red Army during World War II.

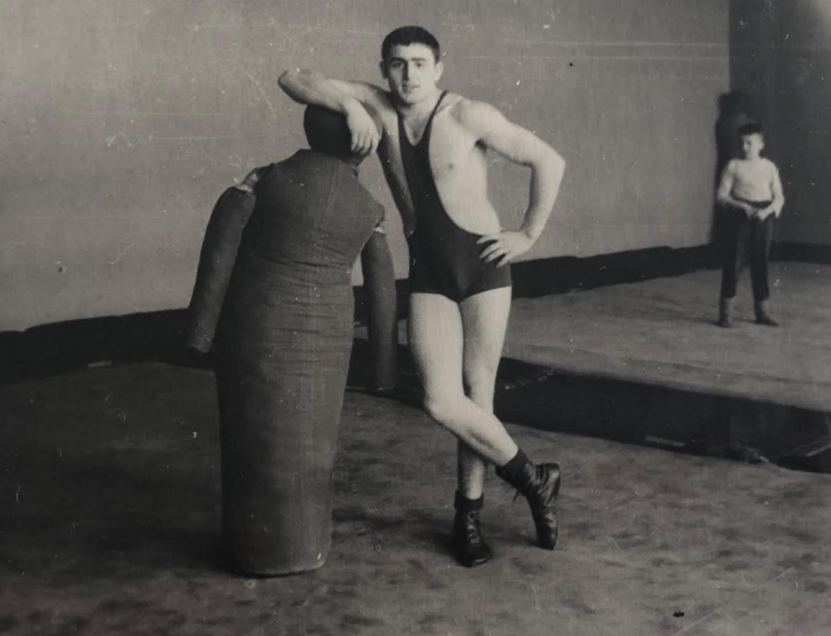

Mark Slavin developed a wide range of interests. He boxed, collected old books and postcards, read Pushkin and Mayakovsky, painted landscapes, played the accordion, sang, danced, and listened to Tchaikovsky, Jewish and Russian folk songs, and even Elvis Presley on foreign radio programs. At the age of nine he saw a wrestling match in the streets of Minsk, was thrilled and persuaded his family to be allowed to take wrestling lessons himself. He was unusually strong and managed to to lift his own father up into the air at the age of just twelve. Two years later, his talent was spotted by sports officials and he was taught at an elite sports school. His sporting successes culminated in 1971 with the title of junior middleweight wrestling champion of the Soviet Union, which made him a medal hope at the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich. Despite his success, Mark Slavin suffered from the prevailing antisemitism. He regularly had to use his athletic prowess to protect himself and his younger brother from physical attacks. His Jewish background and his religion were important to him, and in early 1972 he applied to emigrate and wanted to become a member of the Israeli Olympic team. Until he received permission to leave the country, he had to do without many things. He was banned from competitions and all his titles and certificates rescinded.

In May 1972, however, Mark Slavin and his family were given permission to emigrate. They settled to the north of Tel Aviv. From here, at the first opportunity, Slavin walked the 10 km to the HaPoel sports club in Tel Aviv, without having any knowledge of either the country or the language. He introduced himself and said that he wanted to be part of the Israeli Olympic team. During trial matches, he won against the Israeli Greco-Roman wrestling champion Eliezer Halfin, who had emigrated to Israel from the Soviet Union only three years earlier. He also defeated the Frenchman Daniel Robin, the 1967 world champion, who had won two silver medals at the 1968 Olympics and flew in especially for the match. As a medal hopeful at the Olympics Slavin was fast-tracked to be given Israeli citizenship and was also allowed to train under the coach Moshe Weinberg at the Wingate Institute in Netanya.

After only three months in Israel, Mark Slavin promised his brother Eilik that he would bring a medal back with him before leaving for Munich.

I’m so happy to be here.

Mark Slavin on August 25, 1972, in a letter to his family in Israel, which did not arrive until after his death.

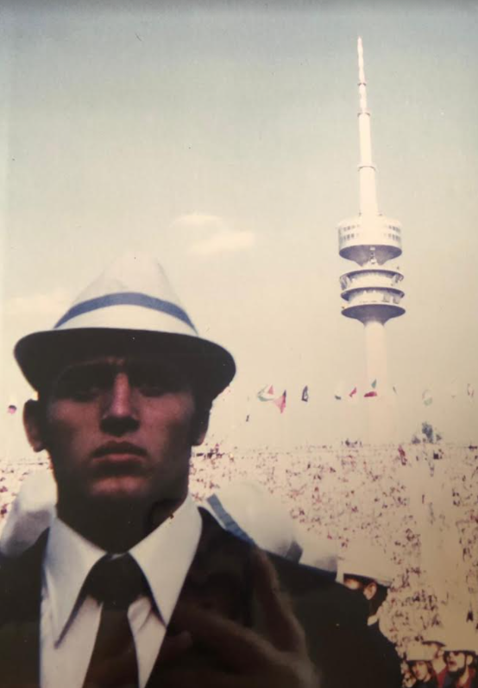

The team, including Eliezer Halfin and Moshe Weinberg, first traveled to Switzerland. On reaching Germany, they visited the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site and Mark Slavin also visited the synagogue on Reichenbachstrasse in Munich. He met his former team colleagues from the Soviet Union as well as wrestlers from the Arab world with which Israel was actually at war, and exchanged badges with them.

Mark Slavin’s Olympic debut was scheduled for September 5. In Israel his parents noticed a newspaper article that morning showing Mark’s coach Moshe Muni Weinberg. They didn’t speak Hebrew at that time, but Slavin’s mother Anna found someone to translate it into Yiddish. In this way they found out that hostages had been taken in the Olympic Village and rushed home to follow the news about their son’s fate late into the night. The next morning it become clear that Mark Slavin had been killed—the youngest of the victims.

Slavin’s letters from Munich to his grandfather Zalman Slavin in Zhlobin (Belarus) and his family in Israel did not arrive until after his murder. His family suffered greatly from his death. However, the following year, Anna Slavin gave birth to a daughter Mika, who was the spitting image of her eldest brother and gave the family a new will to live. Following the death of her parents, she has taken it upon herself to tell the world about her brother’s life and fate. In the meantime, she has two daughters of her own who perpetuate the heritage of their uncle.

Text: Angela Libal; research: Piritta Kleiner, Curator, Memorial to the 1972 Munich Massacre, Bavarian Ministry of Education, Science and the Arts; Translation: Christopher Wynne

TWELVE MONTHS – TWELVE NAMES

50 Years Olympic Massacre Munich

50 years after the Munich Summer Olympics, the Munich Massacre of September 5–6, 1972 is to be commemorated throughout 2022. Every month is dedicated to one victim. A variety of different actions in public spaces is planned, ranging from installations lasting the entire month to activities on one specific day.

September

In September, the Museum Fürstenfeldbruck, in cooperation with the city of Fürstenfeldbruck, is commemorating the murdered wrestler Mark Slavin with a light installation. The installation can be seen from September 1 on the museum’s façade and provides a reference point to the exhibition “Olympia 1972” which can be seen until October 23, 2022, in the Museum/Kunsthaus Fürstenfeldbruck.