Who is speaking Yiddish in the US currently?

Benor points to two speech groups accounting for the majority of US Yiddish speakers today: Elderly holocaust survivors, a generation and speech community in decline, and Hasidim, a prolific, growing population. Within Hasidim there are also gender-related trends of usage patterns: men tend to use Yiddish more than women, and women’s Yiddish tends to be more influenced by English.

Apart from these two groups, there is a niche group of speakers: the so-called Yiddishists. As the name suggests, this particular movement is interested in maintaining the language for the sake of preserving secular Ashkenazic identity. Some Yiddishists learn it as heritage speakers, from parents or grandparents, but more learn it during adulthood, taking it up just as one would any foreign language. Benor referenced Yiddisch Vokh, an immersive summer retreat in Maryland intended for individuals, couples, or families of all ages and religious devoutness. For one week they get to experience “living life in Yiddish.”

“It’s a small group but a mighty one” Benor tells me.

According to Benor, “Yiddish is a thriving language. When people talk about Yiddish as endangered, that’s really not accurate.” It could seem accurate for those living outside of Hasidim, because in that case most of the observable language output is from elderly speakers. On the other hand, a solid base of speakers, namely Hasidic, raise children to learn the language. Children learning Yiddish natively is indicative of a healthy language status.

What about the sheer amount of Yiddish words and phrases that have entered English in both Jewish and non-Jewish speech?

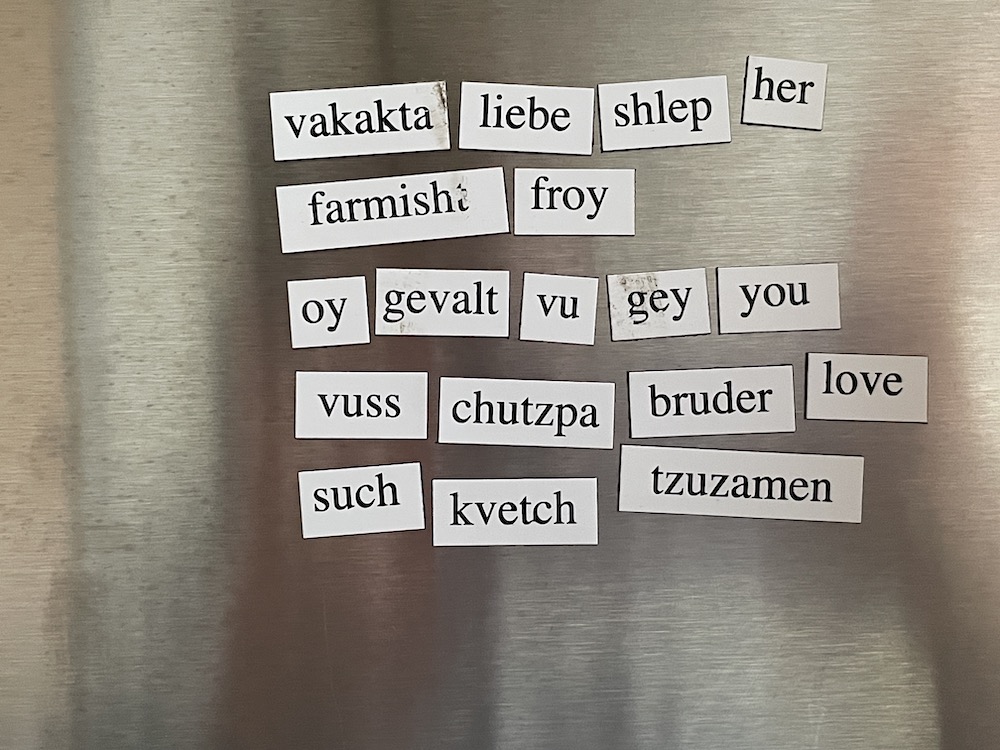

The main way Americans, Jewish and non-Jewish alike, engage with Yiddish today is through loanwords: words that are recruited from one language and integrated into another. Loanwords such as klutz, shmear and even pastrami have fully integrated into English to the point where many Americans are unaware that the words are in fact Yiddish. Other loanwords, for instance macher and heimish, are more commonly used by elderly Jewish speakers.

Geography also plays a role in the influence of Yiddish on English: in densely Jewish populated cities such as New York, Yiddish is more prevalent in non-Jewish speech than elsewhere in the country. For non-Jewish Americans who live in cities with a small Jewish population and influence, an awareness to Yiddish likely can be attributed to media (e.g. in recent TV series such as Unorthodox or The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel), social networks, a commodification of products, and numerous Jewish writers and celebrities who use and popularize certain utterances.

For Benor, such ubiquitous influences can explain why someone in rural America may be familiar with a word like verklempt, without being near a community of Jews who use the word among themselves.

We giggled at the mention of verklempt.

And why do we laugh? What contributes to the humor of Yiddish?

Certain unfamiliar consonant clusters might account for the occasionally clunky or goofy sound of Yiddish to American-English ears.

I speculate that another convincing inference is the common use of Yiddish in Jewish-American stand-up comedy of the early 20th century. Performances were sprinkled with Yiddishisms. Examples include Myron Cohen’s skit of a drunk, disheveled, man trying to navigate an elevator, who he described as personifying the word farblondget, and Lenny Bruce’s intentionally nonsensical “yet knish!” used in one of his bits. Benor agreed that likely such seminal performances gave the use of Yiddish loanwords a particular “comedic orientation.”

Humor itself seems inherent, or maybe just necessary, in context of the plight of Ashkenazi Jews: humor evolved as a way to cope with a long history of persecution. This phenomenon is entangled with the very meanings involved in the Ashkenazi language.

What makes Yiddish so special?

For Benor, this question relates directly to the migrational history which has given Yiddish its status as a fusion language. While the base of Yiddish is Germanic (though distinct from German in several respects e.g. in word-order and pronunciation) Hebrew, Aramaic, Judeo-French and -Italian, Polish, Ukranian, Belarusian, and later English (e.g. with loanwords such as jump, window, and step) have helped shape the language as we know and speak it today. Yiddish has fossilized the geographic and linguistic encounters of Ashkenazim. In the form of loanwords in English, and as a native or foreign language, when using Yiddish one speaks an entire history.

About the author:

Jacqueline Hirsh Greene has been living in Munich as a Master’s student from the USA since September 2020. In her studies of linguistics and literature as well as art history, she deals with, among other things, forms of Jewish-American expression such as the use of Yiddish in English and American pop culture.

Dieser Beitrag entstand als Gastbeitrag. Weitere Beiträge zum Thema „Jiddisch heute“ in deutscher und englischer Sprache finden Sie im Blog und auf unseren Social Media-Kanälen.