During the last years, Abu Hamdan has developed a rich and complex artistic practice, taking the politics of sound, and its juridical status, as its starting point. Both in his collaborations with the interdisciplinary collective Forensics Architecture—with whom he’s worked on numerous investigations, contributing as a ‘sound analyst’—and in his own projects, sound, its materiality, and the threshold of its detectability becomes a terrain where aesthetics and politics intersect.

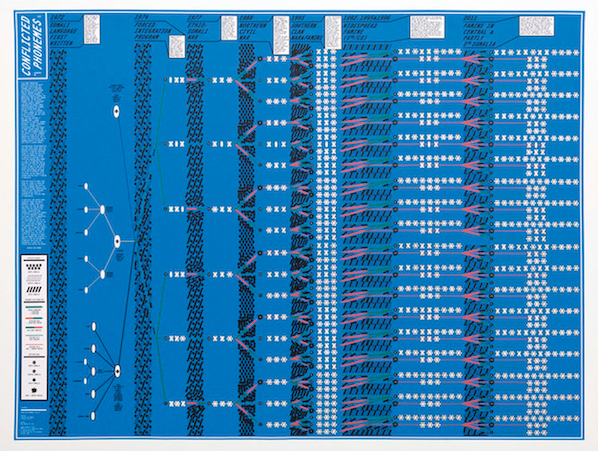

As the biblical story of Shibboleth (Judges 12:5-6) shows, language, the most basic means of communication, can easily become a border that we all carry in our mouth. Sound, intonation, lexicon, are all uses to distinguish between otherwise indistinguishable communities. In his work on view in Say Shibboleth, Conflicted Phonemes (2012), produced in collaboration with graphic designer Janna Ullrich, Abu Hamdan documents the widespread use of language analysis to determine the origin of asylum seekers. Resulting from a meeting with a group of graphic designers, artists, researchers, activists and Somali asylum seekers—whose asylum claims have been rejected by Dutch immigration authorities on the basis of language tests—the work attempts to expose and disseminate the realities and shortcomings of these forensic technologies and practices of “bordering.” The map departs from geographic representation, and instead visualizes the complex relation between a person’s place of birth and linguistic identity, whilst also examining how itinerant and precarious social conditions and cultural exchange might result in a hybridization of accents, thus questioning the efficacy of tests, such as those conducted by the European immigration authorities. These maps were presented to a chief judge working within the Dutch immigration authority, and the research was submitted at a deportation hearing before the UK Asylum and Immigration Tribunal.

Currently, Abu Hamdan is the subject of a large solo-exhibition at the Hamburger Bahnhof museum for contemporary art in Berlin. There, alongside Conflicted Phonemes, several other works exploring the intersection of aesthetics and politics through sound, are on view. This whole time there were no landmines (2017), takes an event which took place in May 2011 on the occupied Golan heights as its starting point. Hamdan filmed in an area known as the “shouting valley” where, due to the resonant acoustics, members from the Druze community who’s families have been separated by the border, are able to communicate using megaphones, their voices carried across the valley as an ‘acoustic bridge’ of sorts.